Updates on States Falling Behind in Dental Hygiene

A few things have changed in states where dental hygiene was lagging behind since the last update.

By luismolinero / stock.adobe.com

The 2014 article titled “The laggards of dental hygiene” by Newkirk and Slim explored how some state dental boards prevent dental hygienists from practicing to the full extent of their training by instituting overly restrictive practice acts.1 The authors discovered most of these states were in the Deep South. This article explores how the practice of dental hygiene has changed over the last 7 years and how the laggard states have fared in catching up with dental hygiene practice acts authorized in the rest of the US.

Because health care works on the basis of hierarchy, levels of change (regionally or by state) are subject to a wide range of resistance. For many decades, starting in the early 1900s, dentistry began as a cottage industry with the dentist at the helm and power being distributed unequally in the context of gendered distribution of labor.

The profession of dental hygiene has been fighting a battle of gender since its inception, especially in laggard states where state dental board members (made up mostly of men), still view hygienists, the majority of whom are women, as not having the “right” skills, competencies, or ability to provide advanced services to the public. This flawed thinking is not supported by evidence, particularly because domestic and international research demonstrates the efficacy of midlevel practitioners in delivering safe, high-quality care. 2, 3

By the time the article “The laggards of dental hygiene” was published, oral health reform to increase access to dental care for underserved Americans was sweeping the nation. States across the country began reducing overly restrictive supervision levels and expanding dental hygiene practice acts to deliver more services to the public, and there was increased activity on the provision of dental care by midlevel dental practitioners, also known as dental therapists. The buzz of these midlevel dental providers took center stage.

Midlevel dental practitioners are similar to physician assistants in medicine. Their work environments include traditional and nontraditional dental settings and clinics, community settings, schools, long-term care facilities, and nursing homes.

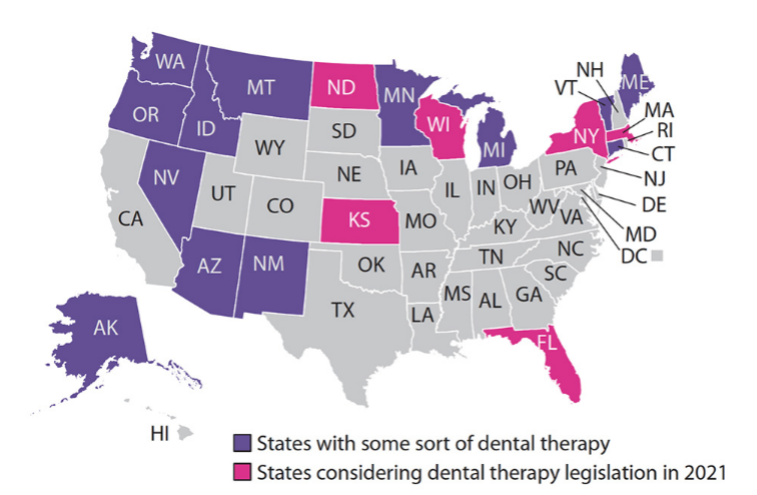

In 2015 the Commission on Dental Accreditation, the same commission that grants accreditation to US dental and dental hygiene programs, adopted accreditation standards for dental therapy. By 2021, 13 states had adopted dental therapy legislation to increase access to the underserved, and 22 states have explored it or are exploring it.

Depending on their state practice act, a dental therapist’s scope of practice may include preventive and therapeutic dental hygiene services, performing routine restorative care including fillings and placing temporary crowns (such as stainless steel crowns on primary teeth), and in some states, they may extract badly diseased, loose primary teeth.

Are laggard states making progress?

But what about the laggard states south of the Mason-Dixon Line? Have they adopted change? In 2014, when “Laggards” was published, 44 states in the US had adopted local anesthesia into their state hygiene practice acts, leaving Delaware, Texas, North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia behind.

Local anesthesia is an expected pain management standard for patients visiting a dental office and it has become an educational standard in dental hygiene programs across the country.

In 2018, the Mississippi State Board of Dental Examiners authorized the University of Mississippi School of Dentistry to begin a 5-year pilot program to teach second-year dental hygiene students the administration of local anesthesia. The school is now into the third year of the pilot program, and once the program is complete, the board hopes to adopt local anesthesia administration into the core curriculum for dental hygiene programs in Mississippi. In 2018, the Alabama Board of Dental Examiners wrote rules to permit licensed dental hygienists to administer local infiltration anesthesia under the direct supervision of a licensed dentist.

In 2021, North Carolina lawmakers introduced a comprehensive bill to expand dental hygiene practice in the state. NC HB 144 establishes standards for the practice of teledentistry, authorizes properly trained dental hygienists to administer local dental anesthesia under the direct supervision of a licensed dentist, and permits certain dental hygienists to practice dental hygiene in schools while working under general supervision. The measure is pending passage in one committee and if cleared, will go to the governor for his signature.

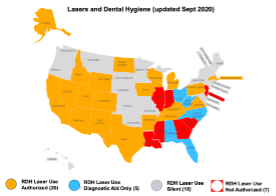

Although it has yet to authorize local anesthesia administered by dental hygienists, in 2015 the Texas State Board of Dental Examiners authorized dental hygienists to use lasers under the direct supervision of a dentist after completing a minimum of 12 hours of in-person continuing education on the dental laser specific to procedures that will be performed. Of those 12 hours, 3 must include simulation training. The state dental board must recognize the education course provider and hygienists must maintain documentation certifying satisfactory course completion.

According to Advanced Laser Training, only 7 states, the majority of which are in the Deep South, do not authorize dental hygienists to use a dental laser. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, dental offices looked for innovative ways to reduce aerosols in the dental setting by having hygienists provide laser bacterial disinfection to disinfect the periodontal pocket before treatment. In addition to treating patients suffering with periodontal disease, dental hygienists use a dental laser to provide pain relief and reduce symptoms of patients suffering with herpetic lesions, aphthous ulcers, and oral mucositis.

But what about Georgia? Since “Laggards” was published, has the Georgia Board of Dentistry embraced change to benefit the public? The simple answer is that it’s complicated.

Although many states have raised the bar for increasing access to oral health services delivered by dental hygienists, laggard state dental boards appear to disregard data and research compared with the more progressive states that have amassed data to make informed decisions. A prime example of this is the administration of local anesthesia delivered by dental hygienists.

Laggard state dental boards fall back on overused, worn-out phrases such as “to protect the public from harm” despite the lack of evidence to support the statement. Another commonly used phrase is “We don’t care what other states do.” Of all the rationalizations made by laggard dental boards, this is the most egregious and self-serving, as it allows board members to put their own interests ahead of the public by disregarding evidence and research data.

Evidence-based decision-making has been around for decades. It is a process for making decisions about a program, practice, or policy that is grounded in the best available research evidence and informed by experiential evidence from the field and relevant contextual evidence that includes the knowledge of subject matter experts.4 In 2013, the American Dental Association adopted a policy on evidence-based dentistry with the goal to help practitioners provide the best care for their patients.5

Neglecting data, research, and testimony from experts allows dental board members to use their personal belief system for decision-making, which focuses on their values, beliefs, history, and current understanding of needs. This “confirmation bias” allows decision-makers to use their preconceived beliefs while ignoring pertinent data.6

An issue that emphasizes how this bias was used for decision-making by the Georgia Board of Dentistry relates to the board deciding whether supervising dentists should be granted the authority to delegate periodontal maintenance procedures to their dental hygienists working under general supervision. The Department of Periodontics at the Dental College of Georgia wrote the board in opposition to this request, stating that its comments were not just the opinion of the board, “but were consistent with the position of the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the American Board of Periodontology (ABP).”

The comment reads, “While there is no problem with the performance of routine prophylaxis by hygienists under General Supervision, we are very concerned about the health consequences if this new request is granted; namely that it will have significant and deleterious long-term consequences for the oral health of citizens of Georgia.”

No supporting evidence for these statements could be found. Neither the AAP nor the ABA has published anything regarding periodontal maintenance delivered by dental hygienists working under general supervision, particularly one that states it causes “significant and deleterious long-term consequences.” Jeffrey Rossmann, DDS, executive director of examinations and professional affairs for the ABP, responded to the inquiry regarding this statement saying, “We are the certifying board of our specialty and do not take a position on dental hygiene utilization.”

Having one’s own opinion about an issue does not become problematic until that opinion is stated as a “position” that is not grounded in fact and is purported as representative of a professional association in order to mislead or manipulate an outcome. Unfortunately, the Georgia Board of Dentistry made its decision on this issue without asking the Department of Periodontics at the Dental College of Georgia to present any supporting evidence, research, or data to support its assertions.

Of the 48 states that have adopted delegated duties of dental hygienists working under the general supervision of a dentist, not one has rescinded a single duty either by rule or statute. Not only do states authorize periodontal maintenance delivered by dental hygienists working under general supervision, but some of them also authorize scaling and root planing, administration of local chemotherapeutic agents, and delivery of local anesthesia.

Logic dictates that if the delegation of these services was in any way harmful to the health of the patient by putting the patient at risk, a literature search would have uncovered a document to support the Dental College of Georgia and Georgia Board of Dentistry argument. Yet none can be found in the commonly used databases and indexes for dentistry.

Dental hygienists are critical oral health professionals utilized in traditional and nontraditional dental settings to address the preventive and therapeutic oral health needs of the public. Across the country, dental hygienists living in progressive states have not only earned professional respect for the services they provide, but they also have accumulated data to show they possess the skills and competencies required to provide advanced services.

As advancements in dental hygiene scope of practice continue to expand to benefit the public at large, let us hope that dental board members in laggard states consider employing data and research for evidence-based decision-making skills that will allow practitioners in their states to provide the best care for their patients. Until then, these states will continue to be the laggards of dental hygiene.