Understanding Dental Implant Design

With a variety of designs and types, it is vital to determine which implant works best for which case.

Understanding Dental Implant Design. Image credit: © MclittleStock; 9george / stock.adobe.com

The mouth is complex, subject to variations in bone density, jaw structure, and overall health. These often complicated variations may present challenges when it comes to patients looking for safe, sturdy, and trusted implant options. For instance, some patients may have robust jawbones with sufficient bone density, making them suitable candidates for traditional dental implants. These implants are surgically placed directly into the jawbone and provide a sturdy foundation for tooth replacement.

Dentsply Sirona’s OmniTaper Implant System combines proven technologies with new innovations for implant treatment in virtually all clinical situations.

One must consider that not all patients possess adequate bone volume or density to support traditional implants. In such cases, alternative options like short or mini dental implants or procedures such as bone grafting may be necessary to augment the bone structure before implant placement. Part of a clinician’s role when considering dental implants for a certain case is looking at the big picture, according to Indraneel Kanaglekar, senior vice president and global dental president of dental implant manufacturer ZimVie.

“When you’re selecting an implant or when selecting an implant company, clinicians look at the technology, they look at the failure rates, the depth of the portfolio, the science behind the implant technology, as well as increasingly the digital workflow technologies and the restorative options available,” Kanaglekar says. “But for a particular case, the most important thing would be the shape and size of the implant.”

Diving Deep on Dental Implants

With the influx of new dental technologies and materials, clinicians are presented with myriad options when it comes to choosing which implant works best. Consider dental implants as a branching path, stemming from 2 main types—endosteal implants and subperiosteal implants. Per the American Academy of Implant Dentistry (AAID), endosteal implants are placed directly in the jawbone and are typically the standard and popular implant choice.1 These implants are usually crafted from titanium in a screw shape.

“Most of our implants are placed at or just below the bone level. And those are called bone-level implants,” Kanaglekar says. “There are some dentists who still prefer to use a tissue-level implant, which means the implant protrudes out of the bone and it sits in the tissue.”

Subperiosteal implants are placed differently, under the gum and on or above the jawbone. These implants are less standard, according to the AAID, but are often appropriate for cases where the patient lacks a healthy natural jawbone and is unable to undergo bone augmentation.¹ Subperiosteal implants involve a metal framework that rests on the jawbone, with posts protruding through the gums to support the artificial teeth. This alternative approach allows for greater flexibility in accommodating patients with compromised bone density or those who may not be suitable candidates for traditional endosteal implants.

The choice between endosteal and subperiosteal implants is influenced by various factors, including the patient’s oral health, bone structure, and personal preferences. Advances in dental technology and materials have further expanded the array of implant options within these 2 main categories. For example, the development of zirconia implants provides an alternative to traditional titanium implants. Zirconia implants may offer esthetic benefits, as they are tooth colored and can blend seamlessly with natural teeth, making them particularly appealing for patients concerned about the visual aspect of dental restorations. It is important to note, however, that zirconia implants are still relatively new to the US market, and questions regarding their efficacy and longevity may be important to consider. One study from Dentistry Journal (Basel) claims that a mixed titanium-zirconia implant did better in terms of survival rates, marginal bone loss, and bleeding on probing than either zirconia or titanium alone.2

When a patient’s jawbone is insufficient or unable to support traditional dental implants, alternative implant types and techniques become essential to restore the structural integrity of the jaw and create a suitable foundation for implant placement. These alternatives focus on stimulating bone growth in the affected areas, effectively preparing the jaw for successful implant integration.

One such technique is bone grafting, a common procedure used in augmenting bone volume. In cases where the patient has experienced bone loss due to factors like trauma, periodontal disease, or atrophy, bone grafts involve transplanting bone tissue from another part of the body, a donor source, or synthetic materials to the deficient area. This procedure promotes the formation of new bone, strengthening and thickening the jawbone to a level that can support dental implants securely. Bone grafting is a versatile solution that caters to various degrees of bone deficiency, allowing clinicians to tailor the treatment to the specific needs of each patient.3 Bone grafting can be supplemented by the use of materials like a bone graft plug, for example the OsteoGen® by Impladent.

The use of guided bone regeneration (GBR) and sinus lifts are techniques designed to enhance bone volume and quality in specific areas of the jaw. GBR involves placing a barrier membrane over the deficient bone area, preventing soft tissue invasion and promoting the growth of new bone. Sinus lifts, on the other hand, are particularly useful for the posterior upper jaw where the bone void created by thenatural sinus cavity may impede implant placement. During a sinus lift, the sinus membrane is lifted and bone graft material is inserted into the space below, encouraging bone growth and creating a more stable foundation for implants.

Other dental implant procedures leverage new technologies for implant placement. Examples include immediately loading implants, mini dental implants, and the All-On-X series of implants.1

Immediate load implants: These implants are as described, crafted with the ability to have a temporary tooth placed on the same day as the dental implant placement. These implants may provide a convenient option for patients who have the structure in place to safely take advantage of this same-day treatment. Systems such as Straumann® TLX Implant System suit both conventional and immediate loading, for optimized chairside efficiency.

Mini dental implants: These smaller implants are designed to provide a less-invasive implant experience for patients. Per the AAID, they are typically used to stabilize a lower denture.¹ MOR®mini implants from Sterngold are designed for simplicity and affordability, all while being designed for immediate loading.

All-On-X implants: Procedures using these implants leverage 4 to 6 positions in the mouth to strategically support a full arch of teeth. This type of implant technique and treatment may reduce treatment time, as it eliminates the cost, time, and added surgery of placing multiple different implants, in favor of placing a few strategic ones.

According to Kanaglekar, the design of dental implants has undergone significant evolution in recent decades, reflecting advancements in materials, technology, and a deeper understanding of biomechanics. One notable aspect of this evolution is the transition from predominantly straight implants to the adoption of tapered designs, each with distinct implications for how they integrate into the oral environment.

“Previously, around 20 to 30 years back, when the implant technology started developing, most of the implants were largely straight, or even if they were tapered, they were tapered at the apical point or at the bottom,” he says. “Over time, the technology has evolved and most of the implants are fully tapered.”

The tapered design enhances primary stability during implant placement, especially in cases where the available bone may be compromised or limited. By gradually widening toward the coronal end, tapered implants engage more surface area within the bone, maximizing initial fixation and reducing the likelihood of micromovements that could hinder osseointegration. This improved stability is particularly beneficial in situations where immediate or early loading of the implant is desired. Mimicking the anatomy of a tooth root, tapered implants distribute occlusal forces more evenly along the surrounding bone. This helps minimize stress concentrations, reducing the risk of complications such as bone resorption or implant failure over time. The biomechanical advantages of tapered implants have led to their widespread acceptance and utilization in various clinical scenarios.4 ZimVie’s T3® PRO Tapered Implants and the TSX™ Implants take advantage of the tapered design to provide enhanced clinical results including more stability and defense against peri-implantitis.

Another factor that impacts implant design is the connection, according to Kanaglekar. “The connection, meaning the screw of the abutment that goes into the implant, what type of connection is that? Now, a simple analogy would be as if it were a Phillips screw or hex screw vs an octagonal screw. It’s similar to that. And there are various types of connections,” he says. “Our implants come with primarily 2 different connections. One is what we call internal hex, and the other connection is named Certain®. We believe both these connections provide an excellent seal, where the bacteria do not enter the implant after placement, while also helping form tissue around the implant and encouraging bone growth around the implant.”

Connections play a vital role in dental implant design as they are critical components that link the implant to the prosthetic structure, such as crowns, bridges, or dentures. The connection between the implant and the prosthetic component is crucial for the overall success, stability, and longevity of the implant-supported restoration.

ZimVie’s T3® PRO Tapered Implant and Encode® Emergence Healing Abutment offer implant solutions for dental clinicians. These products utilize ZimVie’s implant innovations, like Osseotite ® and intraoral scanning visibility, respectively.

More Than Skin Deep: Surface Treatments in Dental Implant Design

Surface treatments are crucial in implant design because they significantly impact osseointegration, which is the direct structural and functional connection between the implant and the surrounding bone. The surface characteristics of dental implants play a pivotal role in determining the success, stability, and long-term performance of the implant.5

“The surface technology that is used to provide roughness to the implant is another place where implants differ from each other,” Kanaglekar says. “At a very high level, there are 2 types of surface technology that you can use to make the implant surface. One is additive surface treatment, where you add some sort of rough coating on the surface. The other is subtractive, where you etch the implant, or you blast the implant and take something out of that surface and make it rougher. Over time, we have come to believe that the subtractive surface roughness technology worked really well for us.”

For ZimVie, 20 years of data have supported its Osseotite® dental implant and its increased contact osteogenesis. It has a unique 1- to 3-µm peak-to-peak surface that leverages an acid-etch process, and per ZimVie’s website, its surface features are specifically designed and sized to entangle fibrin strands of the blood clot.⁶ “What we have tried to do is create an implant that is rougher to the collar–which is the top portion of the implant–and then we still create a small amount of softness on the collar, where it encourages bone growth, but does not become so rough that it attracts bacteria.” Kanaglekar says.

The TSX Implant from ZimVie is designed for immediate extraction and loading, utilizing a hybrid of dual acid-etched and MTX™ surface technologies.

Alternatively, additive treatments use mechanical or chemical processes to add material that changes the surface of the dental implant. There are a variety of methods to adding materials to the surface, including through a superficial addition and through a deeper integration. Integration implies that the material is going directly into the implant’s substrate material, for example, introducing ions of fluoride, whereas a superficial addition typically comes in the form of coating the surface. According to a study done in BioMed Research International, coating techniques can include titanium plasma spraying, plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coating, alumina coating, and biomimetic calcium phosphate coating.7

Although both subtractive and additive are valid techniques in surface treatments, dentistry has shifted to focus on more subtractive measure, Kanaglekar says. “We believe we have some of the best surface technologies on the market. And the reason why the industry typically believes that subtractive surface technologies are better than additive is because there is a belief that sometimes these additive technologies, the particles can later on aggregate or create issues for infection,” he says. “That said, we still have some legacy lines that utilize hydroxyapatite surface coatings. And again, in that sense as well, our surface technology, what we call MP-1® HA is very different. Backed by clinical data, we believe that if you want to go for additive technologies, we believe we have the best available.”

The choice between a superficial addition or deeper integration of materials depends on specific clinical considerations, including the desired outcome, the materials used, and the targeted improvement in implant performance. Each method has its advantages and potential drawbacks, and the decision may be influenced by factors such as the patient’s oral health, bone quality, and the overall treatment plan.

Knowing Which Implant to Use When

Choosing the right dental implant is a critical decision for clinicians and their patients, and several factors can come into play.

“The most important thing would be the shape and size of the implant. Because if it’s a narrow ridge, then you would need a smaller implant. If it’s a thick bone and in the posterior then you would need a bigger implant,” Kanaglekar says. “The size of the implant would also be dependent on the patient anatomy and the level of bone they have.”

Clinicians may want to consider various factors in terms of the implants that they offer. “For the long term, dentists would typically want to look at the history of a particular implant’s failure rate, or long-term survival rates, as well as the science and publications available about the surface technology and about the bone loss or bone preservation around that after the implant is placed, as well as the restorative options that can provide optimum esthetic and functional benefits,” Kanaglekar says.

For instance, mini dental implants may be optimal for patients with less jawbone density who still desire a less invasive procedure. This might be ideal for patients with smaller mouths or any other patient whose jaw mass cannot support traditional dental implants.8

“You will come to a natural conclusion whether, in this case, it’s better to have individual implants or an implant-supported bridge. Typically implant-supported bridge or a full arch treatment would be recommended,” Kanaglekar says. “If you have multiple adjacent teeth that are missing, or your patient is partially edentulous or fully edentulous—if there are, let’s say, 2 teeth missing but there are multiple teeth in between that are healthy and the smile is good, then the dentist is going to recommend 2 different implants even though there are 2 missing teeth. But if it’s adjacent teeth or more than 3 or 4 teeth missing and it’s a partially edentulous case, then you are most likely going to go for an implant-supported bridge or a full implant-supported denture.”

Steps to determining which implant best suits which case may lie in the dental practice’s ability to harness the right technology and tools.

Technology Workflows Bolster Implant Care

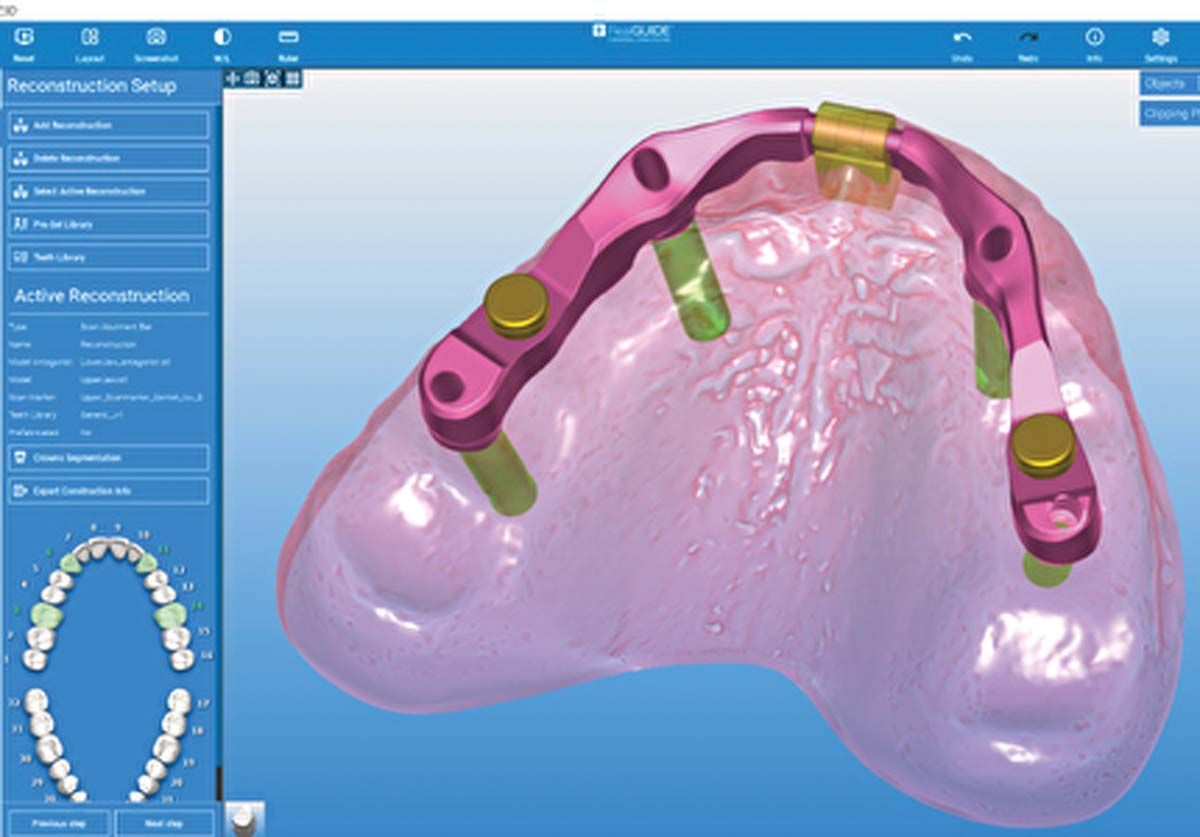

Digital workflows can be key in determining the right type of implant for your patient. From smile visualization programs to software like RealGUIDE™ from ZimVie, there are more options now to find the right fit for the dental practice.

RealGuide from ZimVieis a software module that enables clinicians to design the optimal restorative system for their patients, bolstering the digital implant workflow in the dental practice.

RealGUIDE is a cloud-based software suite that enables implant planning, design, surgical guide design, and other programs. By combining these functionalities in a single platform, RealGUIDE aims to enhance efficiency, accuracy, and collaboration, according to Kanaglekar.

“These days, the best way to assess a case would be to do a comprehensive surgical and restorative planning, which will give you a good idea on not just the shape and size of implant but how and at what angle it should be placed,” he says. “You start with taking a 3Dx-ray or a CBCT scan. We’ll also merge that with an intraoral scan, which gives you a view of the other teeth and the tissue.”

Once those are imported in the software, clinicians can best determine and design which implant will work for the case, assessing the location of nerves, assessing bone density, and moving onward to create a surgical guide for the case. The surgical guide can then be sent to ZimVie, where it can be manufactured or, if the clinician owns a 3D printer, they can print it chairside. Other platforms, such as the Romexis® 3D Implantology from Planmeca, provide platforms that enable both digital implant design and surgical guide design. Planmeca also provides a full implant library, which allows clinicians to keep a database of both implant and surgical guide designs, downloadable from Planmeca’s website.

“Going forward, we’ll continue to innovate on implant design,” Kanaglekar says. “We want to improve our implant offerings in terms of shapes, sizes, technology, but also make sure that these improvements are tied to this end-to-end digital workflow that will improve practice efficiency and restorative comfort.”

References

- Types of implants and techniques. American Academy of Implant Dentistry. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://aaid-implant.org/what-are-dental-implants/types-of-implants-and-techniques/

- Fernandes PRE, Otero AIP, Fernandes JCH, Nassani LM, Castilho RM, de Oliveira Fernandes GV. Clinical performance comparing titanium and titanium-zirconium or zirconia dental implants: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Dent J (Basel). 2022;10(5):83. doi:10.3390/dj10050083

- Weinlaender M. Bone growth around dental implants. Dent Clin North Am. 1991;35(3):585-601.

- Nandini N, Kunusoth R, Alwala AM, Prakash R, Sampreethi S, Katkuri S. Cylindrical implant versus tapered implant: a comparative study. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29675. doi:10.7759/cureus.29675

- Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G, Ferrante L, et al. Surface coatings of dental implants: a review. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14(5):287. doi:10.3390/jfb14050287

- The Osseotite dental implant. ZimVie. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://www.zimvie.com/en/dental/dental-implant-systems/3i-osseotite-implant.html

- Jemat A, Ghazali MJ, Razali M, Otsuka Y. Surface modifications and their effects on titanium dental implants. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:791725. doi:10.1155/2015/791725

- Flanagan D. Rationale for mini dental implant treatment. J Oral Implantol. 2021;47(5):437-444. doi:10.1563/aaid-joi-D-19-00317