How CBCT benefits both you and your patients

Planmeca Viso™ G7 CBCT imaging can improve diagnosis and treatment planning with low patient X-ray dose.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) was first introduced on the market in 2001.¹ Since then, CBCT has become an important technology in dentistry by providing three-dimensional (3D) images with higher spatial resolution and lower radiation than Multidetector Computed Tomography (MDCT). CBCT has replaced extraoral radiographs such as occlusal, Waters, submentovertex and reverse Towne views because these views can be reconstructed from the CBCT scan by software.

The College of Dental Medicine at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center is one of the first academic institutions in the United State using the Planmeca Viso G7 CBCT unit in dentistry. 3D imaging is useful for treatment planning in implant dentistry, orthodontics, endodontics, and oral and maxillofacial surgery. With the variety of clinical applications at the university, Planmeca Viso’s 3x3 cm to 30x30 cm volume sizes made it an ideal solution.

The Planmeca CBCT unit also offers lower patient dose without reduction of image quality.² Lower patient dose is advantageous not only for children who are biologically more sensitive to X-rays but also for all patients.

Related reading: Practice better dentistry with 3D imaging

The following are some cases taken by Planmeca Viso G7 at Columbia. In all cases, conventional, 2D imaging failed to show the lesions clearly, in the unmarked set by Satokot, whereas the Planmeca Viso G7 successfully revealed them.

All intraoral and 2D extraoral radiographs were taken by the Planmeca ProMax® 3D and all CBCT images were taken by the Planmeca Viso G7.

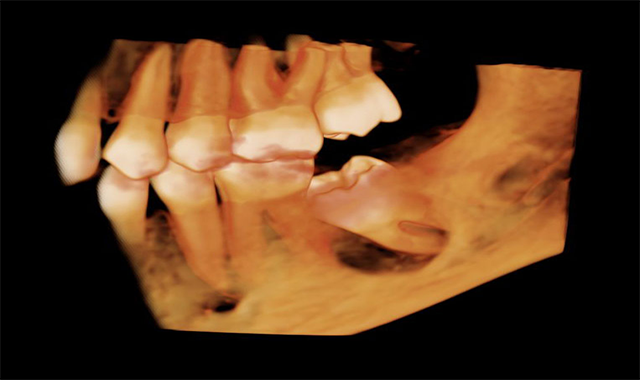

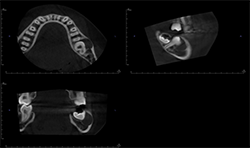

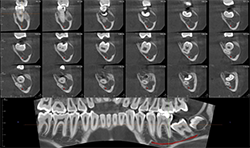

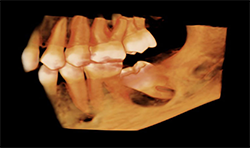

Case 1: 12-year-old boy with delayed eruption of the mandibular left second molar

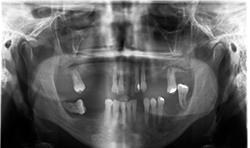

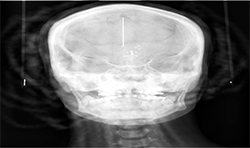

The panoramic radiograph (Fig. 1) shows a well-defined, corticated, radiolucent area mesial to the mandibular left second molar. The inferior alveolar nerve canal is displaced inferiorly.

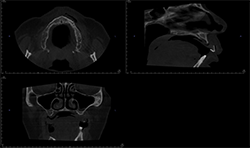

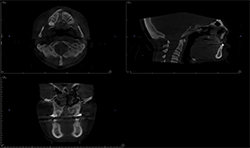

CBCT images of the same patient (Figs. 2A, 2B, 2C) reveal the lesion extends mesial to the third molar follicle, displacing the thinning buccal cortex. The lesion arises from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of the second molar. The inferior alveolar nerve canal is intact. The lesion was treated by surgical removal and submitted for histological examination. The histopathologic diagnosis was a dentigerous cyst.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2A

Fig. 1

Fig. 2B

Fig. 2C

Fig. 2B

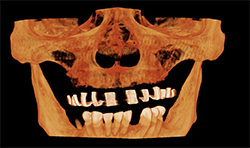

Case 2:66-year-old woman with edentulous maxillae

Two-dimensional imaging can’t evaluate the volume of the alveolar process accurately, especially in the buccolingual direction (Fig. 3)

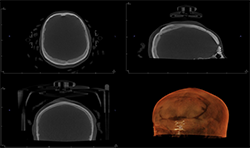

CBCT imaging shows the volume of the alveolar process in any direction for implant treatment planning. (Figs. 4A, 4B) CBCT software allows one to measure the height and width of the alveolar ridge (Fig. 4C). This patient doesn’t have adequate bone volume for implant placement in the posterior left maxilla (Fig. 4D). Due to the severe alveolar ridge resorption, gaining adequate bone volume was recommended.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4A

Fig. 3

Fig. 4B

Fig. 4C

Fig. 4B

Fig. 4D

Fig. 4D

Continued on page two...

Case 3: 18-year-old woman with cleft for orthognathic surgery

Panoramic and cephalometric radiographs are of limited use due to superimposition of anatomical structures (Figs. 5A, 5B, 5C).

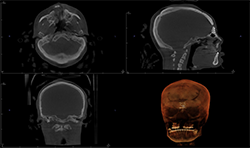

CBCT characterizes the cleft defect more superiorly than 2D imaging (Fig. 6).

The Planmeca Viso G7 CBCT unit and Planmeca Romexis software can stitch two volume scans automatically with one click. The top portion of the skull (Fig. 7A) and the remaining maxillofacial portion (Fig. 6) were stitched to make a single skull volume (Fig. 7B). Multidisciplinary team has been working on this patient. Prosthodontics and oral surgery will plan to manage maxillary alveolar cleft and associated malocclusion following the CBCT images.

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5B

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5C

Fig. 6

Fig. 5C

Fig. 7A

Fig. 7B

Fig. 7A

Related reading: How to use digital technology to make cases easier

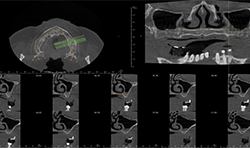

Case 4: 59-year-old woman with pain and sinus tract associated with endodontically treated #14

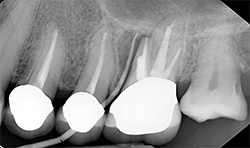

Periapical radiographs (Figs. 8A, 8B) show that radiolucent area around the mesial root of #14 and missing lamina dura. The apical lesion is close to the floor of the left maxillary sinus.

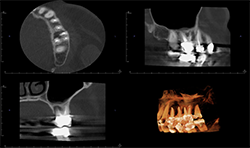

CBCT (Figs. 9A, 9B) reveals the lesion extends from the buccal cortex to the palatal cortex with furcation involvement and involves the palatal root. Mucosal thickening is noted along the floor of the left maxillary sinus, suggesting odontogenic origin. Tooth extraction would be recommended.

Fig. 8A

Fig. 8B

Fig. 8A

FIg. 9A

Fig. 9B

FIg. 9A

Conclusion

CBCT has been essential in contemporary dentistry since its introduction in 2001. CBCT has a small footprint, is more economical than MDCT and gives clear details on bone and teeth.

Despite these benefits, CBCT does have two key limitations. First, gray-scale values in CBCT cannot be reliably converted to Houndsfield Unit (HU) in MDCT. Thus, bone density cannot be compared across the volume. Secondly, soft tissue resolution is poor in CBCT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for soft tissue pathology.

Drawbacks aside, CBCT is still a valuable adjunct to diagnosis and treatment planning, especially in cases where 2D imaging cannot show an abnormality to support the clinical findings.

References

1. Mozzo P, Procacci C, Tacconi A, Martini PT, Andreis IA. A new volumetric CT machine for dental imaging based on the cone-beam technique: preliminary results. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1558-1564.

2. Ludlow JB, Koivisto J. Dosimetry of Orthodontic Diagnostic FOVs Using Low Dose CBCT protocol. International Association for Dental Research General Sesssion. Boston, MA2015.