Vertical or Horizontal? A Travel Photographer's Tricky Question

Horizontals come easy. It is the way we see the world. But sometimes a vertical photo is the best way to capture a subject. So how do you know when to make that choice?

Editor's Note: In this article, travel writer and photographer Eric Anderson, MD, lends insight into the tricky decision of when to shoot a photo as a vertical, rather than a horizontal. The topic has become more and more of an issue lately, as more and more people buy smartphones with powerful cameras. This summer, The Los Angeles Times published a piece on how apps like Snapchat are prompting a new era a vertical video. Before you pull out your pocket camera -- er, smartphone -- read these tips by Dr. Anderson.

The decision whether to shoot a travel scene in a vertical format or not was important in the old days with glossy travel magazines. Slide film and costs were important issues but if travel photographers sent an exclusively horizontal batch of slides to an editor they had just lost the possibility of getting the cover for that story.

“Comic-book pages are vertical, and movie screens are relentlessly horizontal.” Frank Miller, comic-book artist and movie director has said. The difference is supposed to be psychological: the horizontal view allows peripheral vision and makes viewers feel they are in the scene, whereas vertical shots apparently isolate the subject and make it more dramatic. Maybe. I once asked a successful photographer, “When do you think a photographer should shoot a vertical?” He grinned at me and said, “Right after you’ve shot a horizontal!”

Horizontals come easy. It is the way we see the world. And it’s the way the arty magazines publish their photographs either with an incredibly beautiful person looking out of the picture so only part of the face shows or, if the subject is an interesting foreigner in a cave or within a cluttered garage, the photographer will choose an extreme wide angle lens for the exalted “environmental portrait.” But the pictures will be horizontal even though, classically, portraits are shot with the lens of that very name as an 80-110 mm lens focused, of course, on the eyes.

But there are times when you just know you have to shoot a vertical.

Duh! When the subject is almost entirely vertical itself

Those are easy choices. You have the camera turned that way without thinking.

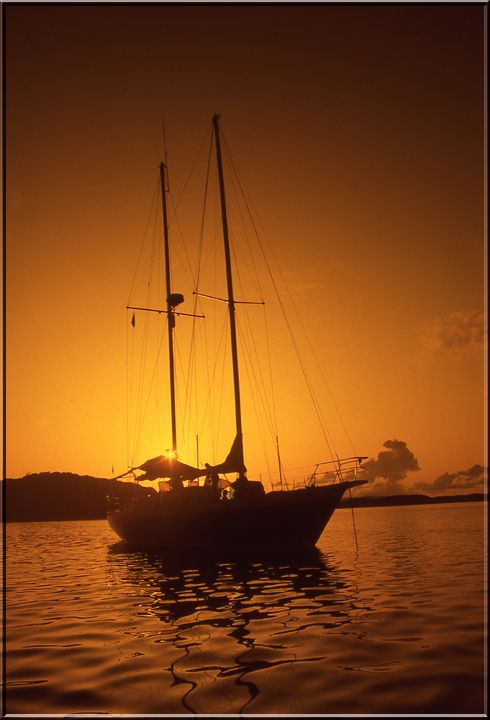

We are surrounded by vertical subjects such as yachts.

A yacht in English Harbor, Antigua

Things created as vertical by our Maker, such as long-stemmed flowers, sometimes used as a landing pad by a flying creature.

When different subjects compete for space

This is when the photographer makes the choice either to move back to get the entire scene in the shot or, aware of the need, turns to vertical and realizes that is a better choice. Sometimes it’s hard to know what will make the photograph, the subject in the foreground or the object farther away that probably is what you first noticed. Do you trivialize the background or middle distance by including something in the foreground or does the combination improve the image by making a scene seem 3D?

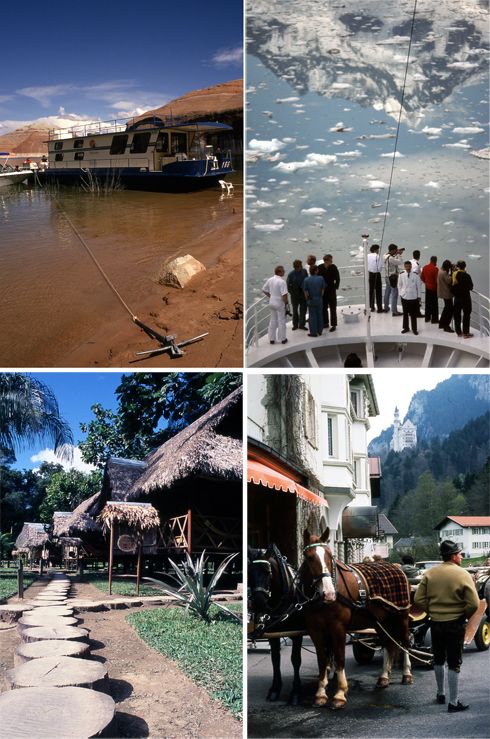

House boating on Lake Powell. Amongst the ice, cruising Alaska. In the Amazon basin at Reserva Amazonia Inkaterra. On Germany’s Romantic Road below Neuschwanstein Castle

Sometimes we paint ourselves into a corner and clutter a scene because we could not get any farther back to make it work as a horizontal. Yet there is a feeling that those who say a vertical makes the photo more isolated and dramatic may be right.

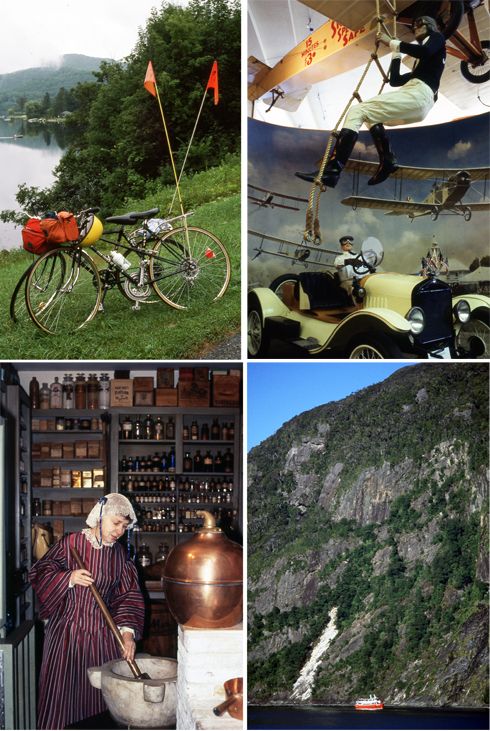

Bicycling in Vermont. Barnstormers at the Aeronautical Museum, San Diego. Polly Mitchell, a “19th Century apothecary” at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont. South Island, New Zealand

Moon over Hohenschwangau Castle, the childhood home of King Ludwig II of Bavaria; it wasn’t fancy enough for him so he built Neuschwanstein Castle which, later, was the model for Disney’s Sleeping Beauty Castle. Opera house, Sydney, Australia. Mont-Saint-Michel, Normandy, France and my borrowed Peugeot. I had to include the car; I was writing an article on it for the tabloid Physicians’ Financial News (now defunct. My writing perhaps?) Loire Valley, Domaine du Dubois

On reviewing a slide collection now digitized, I can usually appreciate why I shot vertical. It’s sometimes obvious but in the Loire Valley Domaine du Dubois above bottom right I had to remember I wanted to show how in France dining is so important that you can have your breakfast beside the pool.

When you can’t crop the original vertical image, it has to stay a vertical

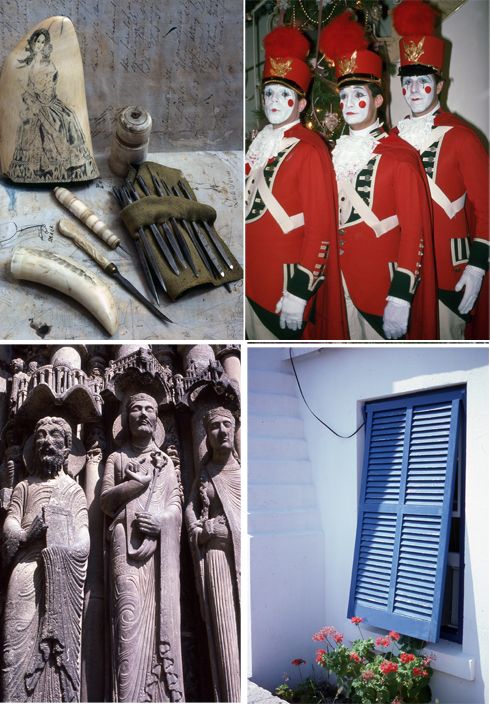

An image may have items top and bottom that cannot be easily cropped such as pieces in the scrimshander kit below. How would you crop the Christmas toy soldiers? Delete their hands or the red pom-poms on their caps? Awful choice. The blue window shade; if you crop the flowers the image loses the contrast. The church figures, however could lose some of their legs but the image is there just to contrast with the Boston toy soldiers.

Scrimshaw exhibit, Sag Harbor, Long Island. Toy Soldier Christmas exhibit Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Boston. Church figures, probably Cologne Cathedral. Bermuda window

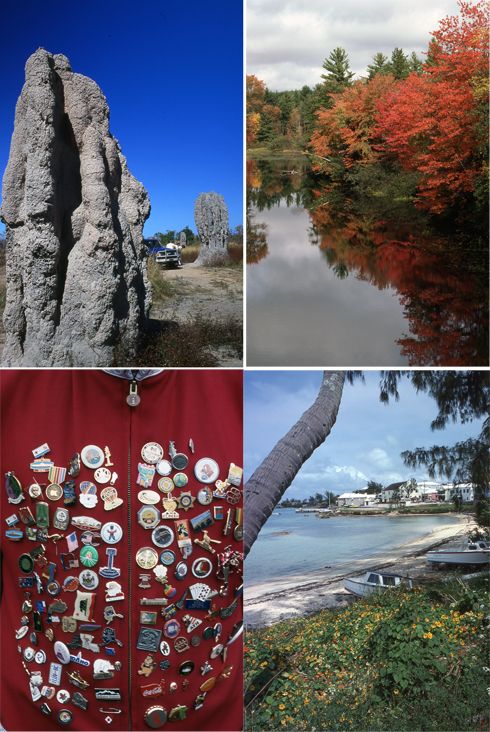

Magnetic Ant colony, Australia, New Hampshire autumn. A guide’s proud vest from our traveling past. Cropping would spoil the impact of the images. But why would you want to crop out the yellow flowers in the Bermuda shot or lose the tree trunk with its leaves that frames the photograph?

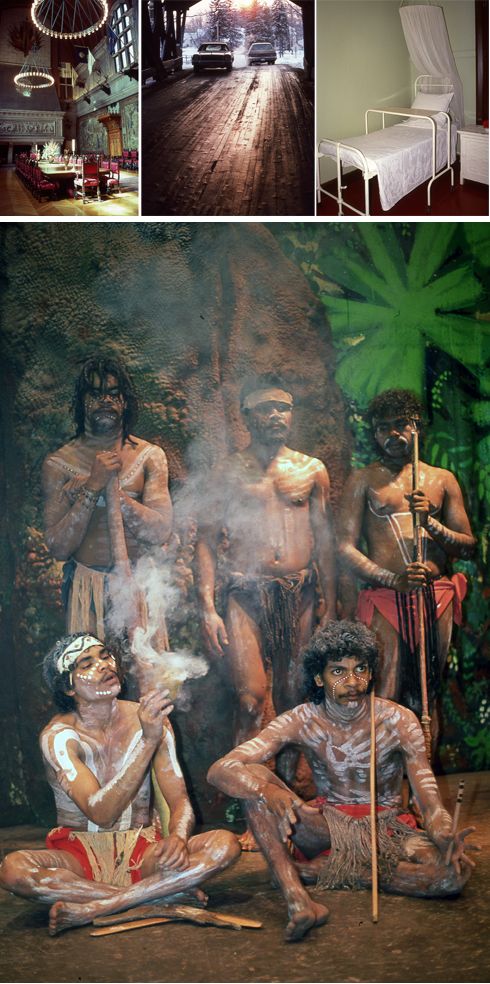

Just as an actor like Meryl Streep can be said to occupy a role completely, so performing acts can fill a photo frame. You could no more crop part of them out than you could dump the chandelier or dining table at San Simeon, the patina of a setting sun on a New England covered bridge, or part of an early hospital bed. The sum of the parts really is greater than the individual parts, for sure.

San Simeon, California. Covered Bridge, New England. Original hospital bed, Alice Springs, Australia. World famous Pamagirri Aboriginal Dancers, Kuranda Station, Near Cairns, Australia

When you want to add spice or drama to a photograph

Perhaps photographers have so much respect for a subject they feel they want to do it justice. You walk up to a scene or an object and you just know you are going to do it as a vertical! A famous old Scottish golfer Laurie Auchterlonie once told me today’s golfers put themselves at a disadvantage driving a golf cart on the course, that in the old days as they walked up to the hole, they were already calculating the lie of the land and what club they would use. So, in the old days of film cameras and multiple lenses a photographer had already decided not only whether it was a vertical or horizontal shot but even what shutter speed and lens opening would be used.

Architecture lends itself often to verticals that emphasize lines.

Topiary, NJ. Rainbow Bridge, Arizona. Mystic Seaport, CT. Kennedy Presidential Library, Boston. B & B Granbury, TX. Eiffel Tower, Paris. Church of Spilled Blood, St Petersburg, Russia. Salzburg Cathedral, maybe. LARGE IMAGE: taken as vertical because the lifeguard was so full of vitality and self-confidence I felt he’d earned a vertical.

When you are compelled by an inner voice to go vertical

So why those verticals?

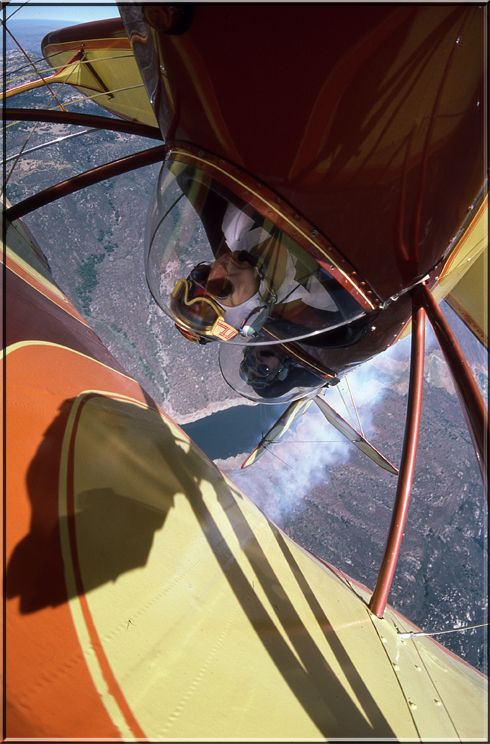

This “Cathedral Spire” on Tahiti just seemed gorgeous — as if our Maker was telling us something – certainly I got a message: Go vertical!

It took me a moment to find the sky (it was top left). I was pressing the remote with my camera screwed into a connection on the wing -- while tossing my cookies from the back seat. I even had the slide labeled TOP because it wasn’t clear which way was up!

I did this montage as a vertical to show my respect for two great figures: Edmund Hillary (1919-2008) who succeeded in being the first with Tenzing atop Everest in 1953 and Robert Scott of the Antarctic (1868-1912) who failed to be the first to reach the South Pole — and died trying.

The Kiwis and the Brits are an understated people, they don’t brag much or ever. Sir Edmund Hillary’s bee keeper cap that he wore on top of the world’s highest mountain seemed tossed into the corner of a huge glass case in the museum in Christchurch, South Island, New Zealand — as if why make a fuss about something no one had done before? And Robert Falcon Scott’s sad story is not something you’d want to read on a cold winter’s night.

But that was the century when men were men.

Photography by the author.

The Andersons, who live in San Diego, are the resident travel & cruise columnists for Physician's Money Digest. Nancy is a former nursing educator, Eric a retired MD. The one-time president of the New Hampshire Academy of Family Physicians, Eric is the only physician in the Society of American Travel Writers. He has also written five books, the last called The Man Who Cried Orange: Stories from a Doctor's Life.

ACTIVA BioACTIVE Bulk Flow Marks Pulpdent’s First Major Product Release in 4 Years

December 12th 2024Next-generation bulk-fill dental restorative raises the standard of care for bulk-fill procedures by providing natural remineralization support, while also overcoming current bulk-fill limitations.