Oral Lichen Planus and Malignant Transformation

Taking a look at some important considerations when assisting patients with oral lichen conditions.

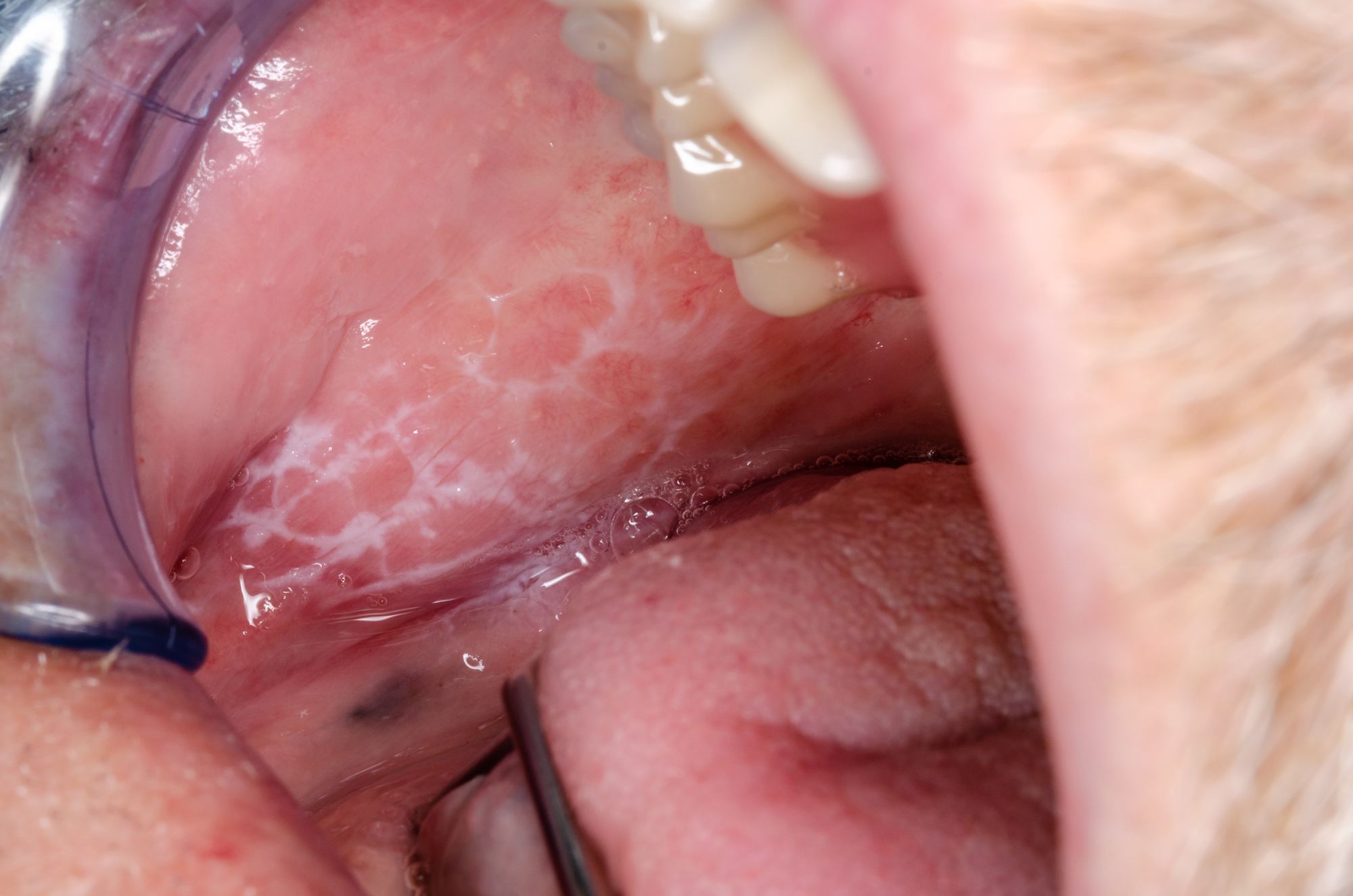

Oral Lichen Planus and Malignant Transformation. Photo courtesy of Dirk/stock.adobe.com.

Have you ever walked around outside and noticed ‘lichens’ on trees? They’re an unsightly but harmless organism that resembles the lacy white patches oftentimes associated with oral lichen planus. Lichen planus is a chronic disease that can affect the skin (including scalp), nails and any lining mucosa and it could be oral, esophageal, vaginal, or skin. Lichen planus only affects about 2% of the population and women over the age of 50 are most often affected.1

The etiology of lichen planus is not completely understood but researchers think that genetics and immunity may be involved and that the body is reacting to an antigen of sorts (like an allergic reaction) within the skin or mucosa. Some researchers view it as an autoimmune disorder, but more research is needed to classify it this way.Severity and subsequent disability caused by lichen planus varies from inconsequential to severe. Skin lesions are typically purple to brown in color, raised as a rash and they can be itchy.1

In evaluating the current evidence on the prevalence of autoimmune disorders in patients with oral lichen planus (OLP) and their magnitude of association, a comorbidity between autoimmune thyroid diseases and OLP and between diabetes mellitus and OLP was found. Studies included in the review, however, were considered low quality.2

The typical OLP we see in patients’ mouths appears in a reticular pattern and is commonly seen on the cheeks as lacy web-like white threads that are slightly raised. These threads are sometimes referred to as Wickham’s Striae. The erosive (atrophic) pattern of OLP can affect any mucosal surface like the cheeks, tongue, and gingiva. It appears as bright red due to the loss of the top layer of the mucosa in the area affected. Individuals with erosive OLP often report discomfort when eating and drinking, especially with extremes of temperature, acidic, coarse, or spicy foods.1

Severe cases of OLP can become ulcerated which may be very painful, even without eating or drinking. There’s 1 other type of lichen planus which is plaque-like and gives the appearance of a dense thickening or the mucosal tissue.1

Pharmalogical management of lichen planus involves the use of corticosteroids, retinoids, photodynamic therapy, topical calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D, and hyaluronic acid. Non-pharmaceutical measures include maintaining good oral hygiene, smoking cessation, and avoidance of appliances that can cause trauma. A recent Cochrane systematic review evaluating the treatment of oral lichen planus concluded that topical corticosteroids may be more effective than placebo for reducing pain of OLP; however, the small number of studies showed the reliability of this finding to be low.3

Lichenoid reactions are not the same as OLP but they can mimic an OLP. They are adverse or allergic reactions that resemble OLP both clinically and microscopically. The list of offending agents causing a lichenoid reaction is extensive and includes medications, oral hygiene products, and occasionally, metallic filling materials. It is not always easy to identify the underlying cause of a lichenoid reaction.1

Malignant Transformation Rate

OLP is considered an oral potentially malignant disorder (OPMD) but its malignant transformation is controversial because of the restrictive criteria for diagnosis.4 Several studies and reviews have suggested a malignant transformation rate of about 1.2%.5

A literature search of papers published (until Nov 2020) on the topic of OLP cases with malignant transformation revealed 89 studies meeting inclusion criteria with 10 high quality studies. Studies were conducted in Australia, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. Sample sizes of the 10 studies ranged from 102-829 patients for a total of 3403 patients. Of the 3403 patients, 3206 had OLP and 197 patients had oral lichenoid lesions (OLL). 86 patients developed oral cancer (80 with OLP and 6 with OLL). The meta-analyses showed an overall malignant transformation rate of 2.28% for OLP and 2.11% for OLL. The certainty of evidence was moderate.

This group of researchers published an earlier review on this topic. Meta-analysis showed a lower malignant transformation rate of 1.14% with OLP and 1.88% with OLL.4 There is some overall discussion about studies being of low quality in both reviews and it is suggested that prospective studies with improved methodology be considered in planning future studies.5

So, what does all of this mean for the average dental practitioner? There doesn’t seem to be anything new in pharmacological management for OLP lesions. If you were unaware that both OLP and OLL are associated with a low risk of malignant transformation, it is important to pay close attention to these lesions if you find any. Follow up at each recare visit during the oral cancer exam, even if the patient isn’t experiencing any discomfort and take photos of the lesions. Occasional biopsies may be needed when lesions persist or if the lesion changes.

References:

Oral Lichen Planus. The American Academy of Oral Medicine. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.aaom.com/oral-lichen-planus.

Oral lichen planus and autoimmune disorders. The Dental Elf. March 9, 2022. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/dentistry/oral-medicine-and-pathology/oral-lichen-planus-autoimmune-disorders/

Interventions for oral lichen planus. The Dental Elf. June 9, 2021. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/dentistry/oral-medicine-and-pathology/interventions-oral-lichen-planus/

Gonzales-Moles MA. Et al. Malignant transformation risk of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral Oncology 2019; 96: 121-130.

Oral lichen planus and malignant transformation. The Dental Elf. November 24, 2021. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/dentistry/oral-medicine-and-pathology/oral-lichen-planus-malignant-transformation/