Dedicated to Katherine “Katie” Slim and Mackenzie “Kenzie” Anderson, beautiful women who died too young. Mackenzie is the daughter of, Tabitha Acret, a dental hygienist living in Australia.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is “abuse directed at a current or former spouse, significant other, partner, girlfriend, or boyfriend.”1 Once termed “domestic violence,” IPV is rarely if ever mentioned in dentistry. Dental professionals probably meet victims of IPV without knowing it, but we may find clues when reviewing a patient’s medical history.

This topic is very close to my heart—about 1 year ago, I lost my daughter to IPV. Approximately 2 years before she died, my daughter, Katie had been physically and mentally abused by a partner. Although she did not die directly as a result of IPV, she was never able to stop feeling responsible for the abuse. Trying to live with that distress made her chronically anxious and depressed, and it continued to contribute to her mental and physical decline until she ultimately passed at the age of 33.

The loss of a child is one of the worst things that can happen to a parent. Death also has a profound effect on relatives, friends, coworkers—even strangers. As I grieved for Katie, I was startled one day by a message on Facebook from a dental hygienist in Australia, who said that her daughter had just been fatally wounded by an ex-boyfriend outside her apartment in Newcastle, New South Wales. Mackenzie, a 21-year-old single mother, had struggled as Katie had.

Yet these 2 young women are not alone. Research indicates that one-third of women globally experience domestic violence, which is considered a human rights violation.2 Young women like Katie and Mackenzie are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, especially if those women are financially dependent on their abusive partners.3

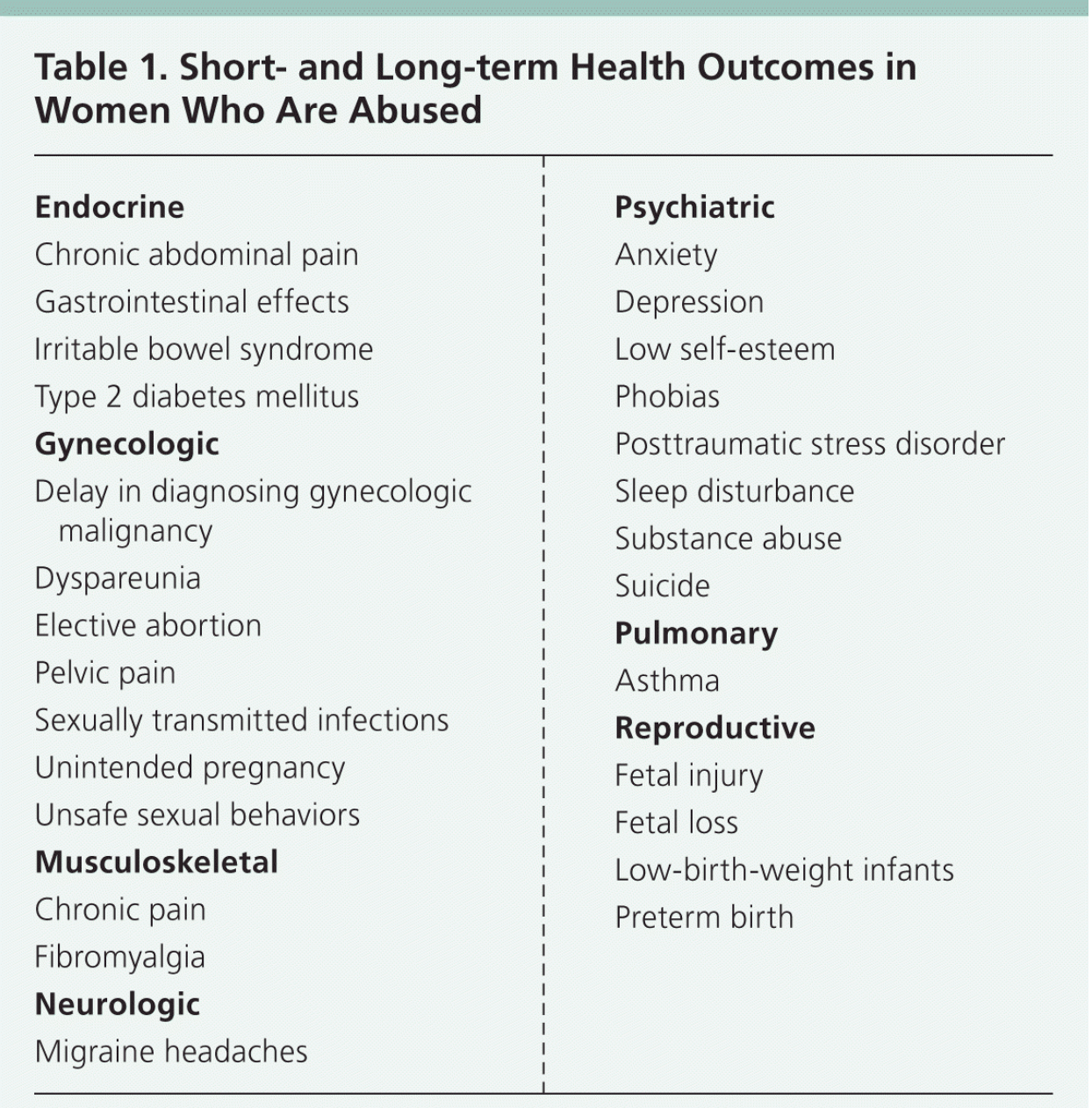

A serious social problem worldwide, IPV has devastating consequences for victims—physically, psychologically, and financially.4 IPV is sometimes difficult to identify, and many cases go unreported, either to health professionals or legal authorities.5 An abused person often feels alone and isolated and experiences lingering adverse effects, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.1 Physical conditions linked to IPV include migraines, arthritis, asthma, chronic pain, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, and digestive and heart problems1 (Table 1). Cognitive changes from traumatic brain injuries as the result of abuse are also an area of concern.6 These are not the only consequences of IPV; physical injuries can often be severe or life-threatening, and about one-third of “female murder victims have been killed by intimate partners.”6

In response to widespread instances of IPV, communities across the United States have created a broad range of resources to support survivors and their families.6 These services include advocacy, shelters, transitional housing, outreach, and counseling services.6 Since the onset of COVID-19, there has been an increased demand for these types of services, adding to an already strained network of support.4 Now, domestic violence programs—which offer housing and foster dignity and socioemotional well-being—are facing budget cuts, staffing shortages, and other difficulties.6,7

The economic control tactics employed by abusers include preventing victims from working, sabotaging their job or housing, and ruining their credit, all of which make leaving home or the relationship very difficult.7

IPV in Dentistry

In 1976, the Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act became the first piece of legislation dedicated to combating domestic violence in the United Kingdom. The United States Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act in 1994 and expanded upon it in 2000 and 2005, creating programs and resources for victims and seeking to hold perpetrators of domestic abuse and violence accountable. In 1996, the Lautenberg Amendment to the Gun Control Act of 1968 went into effect, banning possession of guns by individuals convicted of domestic abuse. All 50 states have passed versions of these laws to penalize domestic abusers and protect vulnerable populations. In addition, many states have civil laws that allow IPV victims to file restraining/protective orders.

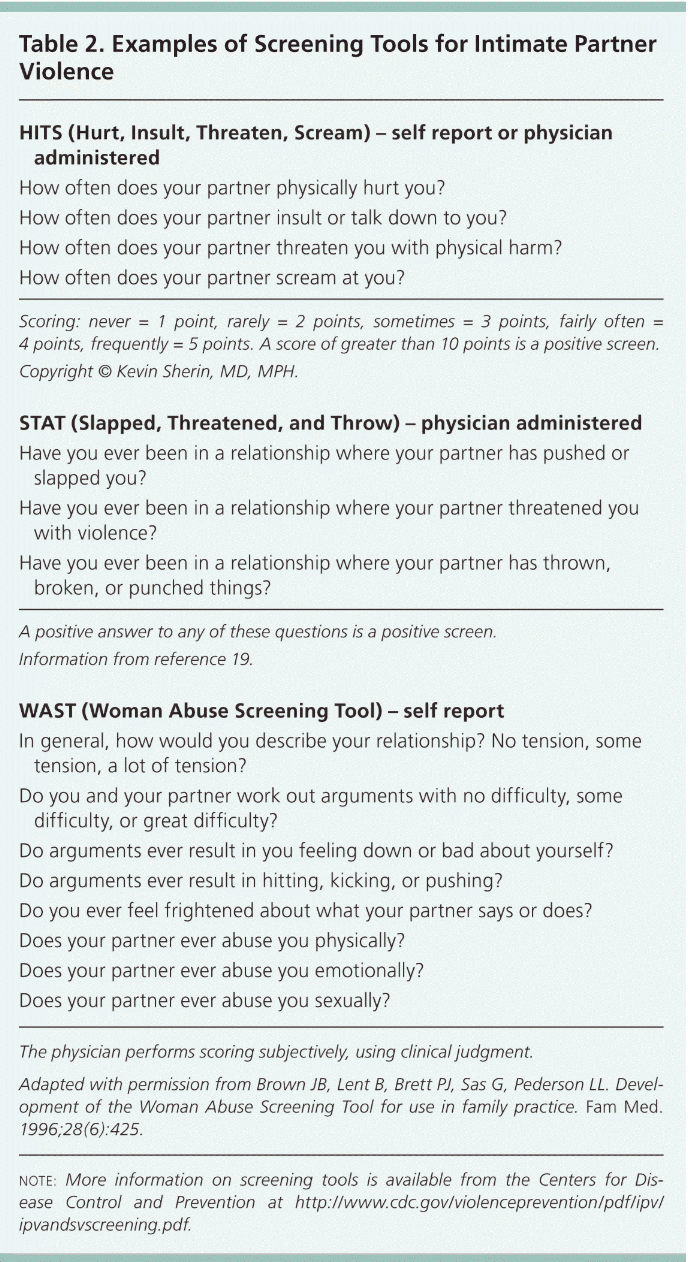

Research on the role of the health care system with regard to IPV is insufficient as many instances go unreported, however, it is estimated that about 20-30% of American women have experienced IPV in their lifetime.8 The US Preventive Services Task Force began recommending routine screening for IPV in female patients of childbearing age with validated IPV screening instruments starting in 2013.8 Such screening tools may be limited based on whether a patient can admit they are in an abusive relationship or if they fear retaliation from their abuser.8 However, this should not dissuade clinicians from regularly screening patients with the tools available (Table 2).8

A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Dental Association found that almost all dentists surveyed did not include IPV screening questions on patient history forms and more than half of dentists did not know where to refer patients who were experiencing IPV.9 Additionally, more than half of dentists surveyed did not feel that IPV screening should be part of their roles as health care providers.9

Dental exams can be an important setting for identifying patients who may be survivors of IPV or currently experiencing IPV, given that common IPV injuries are located on the face and head.9 Bite marks, bruising of the neck and palates, tearing of the labial frenum and/or mucosal lining, lacerations, discolored teeth, traumatic tooth or jaw fractures, and more are common orofacial signs of abuse that can be identified during a dental exam.9

Coercive Control

IPV isn’t always physical. Abuse can come in the form of coercive control, a behavior that exploits, dominates, or creates dependency in the victim.10 Unlike in the UK, where it’s been illegal since 2015, coercive control is legal in the US unless a crime has been committed. Approximately 60% to 80% of women who seek help for IPV have experienced coercive control, which involves these behaviors:11

- isolating from their support system

- monitoring victim activity throughout the day

- denying freedom and autonomy

- gaslighting (causing victims to doubt their thoughts and memories)

- name-calling and put-downs

- limiting access to money

- reinforcing traditional gender roles

- turning children against him/her

- controlling eating, sleeping, or bathroom use

- making jealous accusations, being possessive

- regulating the couple’s sexual relationship

- threatening children or pets

Approach to Patients Experiencing IPV

If a patient screens positive for IPV, they may exhibit a myriad of responses.8 Patients may not be ready to leave the relationship for emotional reasons or due to financial or safety concerns and “most homicides by an intimate partner occur in the year after the abused partner leaves the relationship.”8 No matter their reaction, it is important that clinicians and staff be supportive and provide resources or intervention services.8 Table 3 offers suggestions on how to approach IPV with a female patient.

The following 5-question assessment measures the risk of immediate harm; if a patient answers “yes” to at least 3 of these questions, they are to be considered at high risk of immediate harm.8

- Has the physical violence increased over the past 6 months?

- Has your partner used a weapon or threatened you with a weapon?

- Do you believe your partner is capable of killing you?

- Have you been beaten while pregnant?

- Is your partner violently and constantly jealous of you?

A list of resources should be given to the patient in the event they are in immediate danger (see sidebar). Another step is to implement a safety plan to help the individual leave if the situation worsens.8 This safety plan may include making copies of important documents, securing funds, packing essential items, and making copies of keys.8 The patient should also identify a safe place to stay that is out of harm’s way.8

IPV National Resources

- Futures Without Violence offers posters, brochures, and safety planning cards. futureswithoutviolence.org

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence ncadv.org

- National Domestic Violence Hotline offers calling, texting, or online chatting.

- Call: 1-800-799-SAFE (7233)

- Text "START" to 88788

- Chat: online at thehotline.org

Set up a library in the reception area that includes books on IPV/coercive control and the phone number of the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Health care providers are among those professionals a patient is most likely to trust with issues such as IPV, and we’re also in a position to support children and elderly patients who have been exposed to violence within their families.12

The American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry Charitable Foundation helps victims of domestic violence through its “Give Back a Smile” program (givebackasmile.com), which has fashioned more than 2000 dental restorations since it began operating in 1999.

References

- Understanding intimate partner violence. Harvard Health Online. January 1, 2021. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.health.harvard.edu/womens-health/understanding-intimate-partner-violence

- AmelBarez M, Babazadeh R, LatifnejadRoudsari R, Mousavi Bazaz M, MirzaiiNajmabadi K. Women’s strategies for managing domestic violence during pregnancy: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2022:19(1):58. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01276-8

- Conner DH. Financial freedom: women, money, and domestic abuse. Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 2014(20):339-397. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1380&context=wmjowl

- Global perspectives on intimate partner violence and safety in the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. June 17, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/multimedia-article/global-perspectives-on-intimate-partner-violence-and-safety-in-the-home-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- Huecker MR, King KC, Jordan GA, Smock W. Domestic Violence. StatPearls Publishing, 2022. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499891/

- Sullivan, C. Examining the work of domestic violence programs within a “social and emotional well-being promotion” conceptual framework. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence; 2016. Accessed July 22, 2022. https://www.dvevidenceproject.org/wp-content/uploads/DVEvidence-Services-ConceptualFramework-2016.pdf

- Penti B, Timmons J, Adams D. The role of the physician when a patient discloses intimate partner violence perpetration: a literature review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(4):635-644. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.04.170440

- Dicola D,Spaar E. Intimate partner violence. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(8):646-651.

- Parish C, Pereyra M, Abel S, Siegel K, Pollack H, Metsch L. Intimate partner violence in the dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc.2018;149(2):112-121. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2017.09.003

- Richards L. So, what exactly is coercive control? Laura Richards blog. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.laurarichards.co.uk/coercive-control/

- How to recognize coercive control. Healthline. Accessed October 2019. https://www.healthline.com/health/coercive-control#controlling-money

- Kalra N, Hooker L, Reisenhofer S, Di Tanna GL, García-Moreno C. Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5(5):CD012423. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012423.pub2