Disinfection vs Sterilization: What's the difference?

What is different about these two processes, and how should each be applied in a practice?

Sterilization vs. Disinfection: What’s the difference?

What is different about these two processes, and how should each be applied in a practice

At first glance, "sterilization" and "disinfection" have the same definition. However, in the dental practice, they are used to express differing levels of protection against infection and there is an inherent usage difference between each.

Terminology

So, what’s the difference?

“A disinfectant kills microorganisms, but not the spores,” explains Jackie Dorst, RDH, BS, a “Safe Practices” infection prevention consultant and speaker. “Microorganisms can form spores. A spore has a protective membrane around it-or a hard shell-that protects the microorganisms from disinfectant chemicals. So, the definition is, basically, that a disinfectant kills vegetative microorganisms, but not the spores.

“Sterilization means that all life forms are killed, including the hard-to-kill spores,” she continues. “It’s referred to as asepsis-or it’s a sterile environment-meaning that you’ve reduced all of those vegetative and spore-forming microorganisms. They don’t survive and they cannot transmit or reproduce anymore.”

So why not just go all-in and sterilize everything? For some items, it is neither appropriate nor possible.

“For large items and surfaces that don’t come in contact with patients during the medical procedure, it’s adequate to disinfect those and that is much faster to do,” Dorst says. “It saves a lot of time and it saves a lot of money. And there are many items that cannot be sterilized, because of being damaged by heat or that they’re just so large. For instance, you couldn’t get the whole patient chair in an autoclave to sterilize it. And being able to disinfect that surface gives adequate protection to prevent the disease transmission from one patient to the next patient or the clinicians that are providing care.”

For many applications, disinfection is enough to provide protection from infection.

“Think of a disinfectant as a pesticide,” Dorst says. “Disinfectants are chemicals that kill microorganisms on inanimate surfaces. Surface disinfectant chemicals are not for use on items that go in the patient’s mouth. Disinfectant chemicals are toxic, just like pesticides are toxic. Items that go into the patient’s mouth must be sterilized so that they do not transmit microorganisms to the patient. Or, if they are not heat-tolerant, the items are cleaned and a liquid chemical sterilant is used, according to the manufacturer’s IFU and state laws.”

Chemical sterilants exist, but they take time, are toxic, and must be precisely used. Liquid chemical sterilants must be thoroughly rinsed after soaking an item, which could take six-10 hours, Dorst explains.

Once the sterilant has done its job, it can be easily undone if the proper steps are not observed.

“The chemically sterilized item must be rinsed with sterile water, and often I will see items taken out of a sterilization solution and then rinsed with tap water,” Dorst notes. “Tap water is clean and it’s safe to drink, but, as defined by the water treatment facilities, potable water still has up to 500 colony-forming units per milliliter of water. So, if you rinse it with tap water, then that the item that you just chemically sterilized gets contaminated.”

One versus the other

It’s not up to clinicians to decide which items in the practice are disinfected and which are sterilized. There is precise guidance as to which items are processed in which way.

“Understanding which items need to be sterilized and which can be disinfected is the first step,” Mary Borg-Bartlett, president of SafeLink Consulting says. “The CDC provides excellent guidance for dentistry regarding the classification of Critical, Semi-critical, and Non-critical items. Once the classification is determined, then the correct method for decontamination can be selected.”

The CDC classification guidelines are as follows:

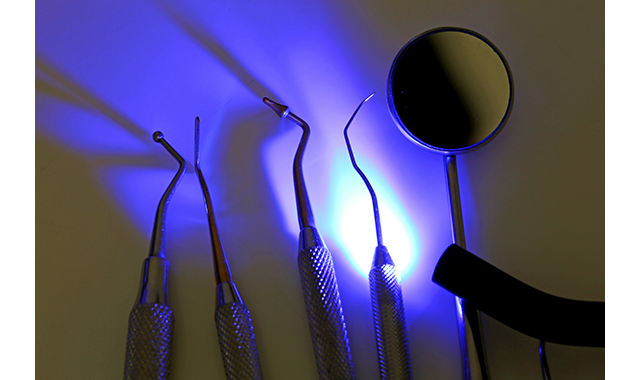

- Critical instruments include forceps, scalpels, bone chisels, scalers, and surgical burs. These are items that penetrate soft tissue or bone or enter/contact the bloodstream.

- Semi-critical instruments don’t penetrate soft tissues or bone but do contact mucous membranes or non-intact skin. These items include mirrors, reusable impression trays, digital radiography sensors, intraoral cameras, and lasers. They should be sterilized after each use.

- Non-critical items only come into contact with intact skin and would include x-ray heads, blood pressure cuffs. These can be reprocessed between patients after proper decontamination.

Proper processing instructions start with the item’s manufacturer and Dorst says that these instructions should be given priority.

“Even the CDC says refer to the manufacturer’s instructions for use. And if the manufacturer does not provide instructions for use, then that item must be considered single-use, meaning, that it cannot be sterilized. The CDC goes a step further stating, ‘If a semi-critical item is heat-sensitive, DHCP should replace it with a heat-tolerant or disposable alternative. If none are available, it should, at a minimum, be processed using high-level disinfection (liquid chemical sterilant).’”

Continue reading on the next page...

Best practices

How do DHCP check to ensure items have been properly sterilized or disinfected? Dorst suggests monitoring the sterilizer system by doing a spore test at least once a week.

“And I would certainly recommend doing a spore test or a category five integrator on all surgical loads, she adds. “If you’re sterilizing an implant kit, I would want to know that the sterilizer load has passed sterilization tests before using it on a patient because that is a surgical kit used implanting a device in the body. The spore test is the ultimate definitive test for sterilization. And then, of course, putting an indicator test inside of each package to validate that sterilizing agent entered that package and touched the instruments to achieve sterilization is critical.”

Checking one’s work and knowing when to use one method versus another is straightforward, but there are still common areas in which practices seem to fumble. For the most part, dental practice staff follows CDC guidelines, Borg-Bartlett observes, but there is room for improvement in the following areas:

- Tracking of autoclave spore culture monitoring: The lab that performs the testing usually emails the results to someone at the practice. This individual doesn’t always provide it to the person who is mailing in the monitoring envelope. The concern is a lack of tracking the results weekly to ensure that all results have been received. This is also good support if this process is challenged by anyone.

- Prevention of moisture in sterilized pouches and wet paper on wrapped cassettes: The concern is that the sterilization can be compromised and not complete if moisture is in the pouch or the wrapping on cassettes is wet after sterilization. Also, instruments may rust which results in having to replace them. Here are some of the causes that should be addressed if moisture is noted:

- Instruments are not dry when placed into pouches or cassettes

- Pouches or cassettes are over-loaded

- Autoclave is over-loaded

- Pouches are not placed into autoclave correctly-placing pouches in paper-side down allows for better drying and is even recommended by some autoclave manufacturers

- Items are removed prior to completion of drying cycle

- Autoclave is in need of maintenance

- Lack of evidence of internal sterilization: Concern is that chemical indicators are not placed inside wrapped cassettes or pouches if they don’t have internal indicators. Typically, the wrapped cassettes have tape placed on the outside of the wrapping which indicates the external sterilization. An indicator needs to be placed inside the wrapping.

- Use of an intermediate-level disinfectant that is EPA-registered and labeled tuberculocidal on semi-critical items that cannot withstand heat: The CDC states that these are the requirements for an intermediate-level disinfectant. The TB kill is what is considered the baseline time for an item to remain wet for it to be properly disinfected.

- Surfaces and/or equipment must be cleaned thoroughly to remove any organic materials in blood and saliva that can inhibit proper disinfection: It’s necessary to read the label on the disinfectant, whether it’s a liquid spray or wipes, to determine if a clean surface is necessary. In most cases, it is, therefore, the staff must either use a spray then wipe to clean the surface and then spray again and leave to dry or wipe with a new wipe and leave to dry. Some products may state they are one-step, however, if the product states there must be a clean surface, then the cleaning procedure must be followed.

- Documentation of sterilization process on pouches and/or cassettes, such as date, time or cycle, and which autoclave was used if more than one in service: This information can be extremely helpful in the event of a notice of a spore culture failure. Without this information, then all sterilized instruments must be re-sterilized. With this information, the date and which autoclave was used narrows down the amount of re-sterilization required.

Ultimately, disinfection and sterilization are indicated for specific processes and they require properly trained personnel to know the difference and the methods by which they are achieved.

“It’s important for the sterilization tech for all of the dental clinicians to understand the sterilization process and understand how to validate and monitor the process to make certain that it works,” Dorst says. “For instance, they may be using that cold-sterilization chemical and they’re not rinsing with sterile water afterward. They may also be putting wet items in that cold sterilization chemical that they use for 28 days. Well, those wet items can dilute the content of the glutaraldehyde to a point that it’s not achieving sterilization. So, they should be testing the glutaraldehyde by using a test strip to monitor that the liquid still has adequate chemical concentration. Sterilization is a complex process and it does require technical training for the dental professionals who are sterilizing the instruments and disinfecting the operatories.”

On the surface, “disinfect” and “sterilize” having similar meanings. But it’s important to remember that each definition carries with it a process that is vital to the dental practice. Professionals must know when and how to achieve disinfection or sterilization to ensure proper patient protection.