Cosmetic Dentist Maximizes Cross-Cultural Experiences

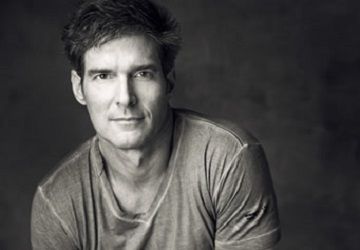

Trey Wilson, DDS, has taken his holistic approach to dentistry around the world to help those living in underserved areas.

By his own admission, Trey Wilson, DDS, was a precocious child--a first born who figured he needed to know what he wanted to do with his life by age 14.

So it came as no surprise when Dr. Wilson--following his first art show and some encouragement from his teacher to pursue more training in sculpture--announced he wanted to be a sculptor.

“I really did enjoy it,” says Dr. Wilson, today a highly successful New York City-based cosmetic dentist. “And I still do.”

But his father explained that it would be very challenging to live a full and successful life as a sculptor, and offered an alternative plan.

“Why don’t you think of something else that has a sculptural component to it,” he suggested.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Holistic approach

Dr. Wilson takes a holistic approach to dental health, as noted in his motto: “Dentistry from the heart, for the heart.” And he attributes that approach to time spent as a younger man in Egypt, Africa and numerous other countries.

“You start speaking with the shaman and the tribesmen—people who were healers in the villages and cities,” Dr. Wilson says. “They were using botanically based solutions to solve a lot of problems, and I really enjoy learning from the sages who preceded us. It’s also one of the reasons I became interested in botany and horticulture.”

In fact, Dr. Wilson recently completed training at Bowman’s Hill Wildflower Preserve, where he also volunteers, and talks about a portion of the park called the Medicinal Trail.

“Nature has provided us so many different ways to be healed,” he explains. “I try to really embrace that in my practice. And I think it’s been a really rich and gratifying experience for my patients and I over the years.”

No small surprise, then, that Dr. Wilson has sometimes been referred to as the dental care evangelist. He says it’s a label that fits his attitude.

“It’s really about taking the message of dental health, and the importance of dental health, and the important part it plays in the overall wellness in our lives,” Dr. Wilson says.

Stopping the world

It was 1995 when Dr. Wilson recalls having a “stop the world I want to get off experience.” He had an opportunity to travel for a month in Africa, and for a student of anthropology, it was a life-changing experience.

“The guide we had enabled me to go into places that I think most white persons were not able to,” Dr. Wilson recalls. “And I had the opportunity to observe things like dental health.”

What Dr. Wilson observed, and what he found incredibly interesting, was that the elder tribesmen had all their teeth while the children were losing their teeth—ravaged by tooth decay.

“I recognized that it was diet,” Dr. Wilson says. “Seventy-year olds had largely managed to keep their teeth because they had diet control. Diet, in and of itself, was changing the depiction of health and disease in these communities.”

Those images stayed with him.

Tabasamu means smile

In 2004, when Dr. Wilson’s church mentor in Bucks County, PA, gave a presentation on the importance of being more world-focused in an outreach program, he founded Tabasamu (smile in Swahili)—a non-profit outreach project that brings dental health education and preventive care to underserved communities in Kenya, Guatemala and Haiti.

“It was really a supernatural experience,” Dr. Wilson says.

He wrote letters to his parents’ friends, his high school friends, and people at his church announcing what he wanted to do and asking for donations. He ended up with approximately $35,000 just from writing letters, and the donation of equipment from Doylestown Hospital. For the first three years he was providing free dental care.

“We built these ambulatory dental units in two places, and we advertised through the locals and churches that free dental care was being provided,” Dr. Wilson explains. “And then we’d pack it all up and put it away in storage before our departure.”

The response was incredible. When Dr. Wilson and his colleagues arrived at the ambulatory dental units about 9 a.m., there were close to 300 people waiting in line.

“We started doing ad hoc dental education,” he recalls. “We took some of our volunteers, who were not dentists nor dental hygienists but had gone through our training programs, into the crowds with a toothbrush and a translator and started doing dental education.”

But just providing free dental care didn’t change the complexion of health in those regions.

“People don’t change what they don’t value, and they don’t value what they don’t understand,” Dr. Wilson explains.

Those living classrooms, where the dental education took place, was where the locals began learning that behavior and the choices they made were the keys to creating a healthier community. So Dr. Wilson went back to the drawing board and developed platforms for education that could be brought to different parts of the world as a new paradigm for making communities healthier.

“It’s a real cross-cultural experience,” he says. “And 80 percent of the people we bring with us to do these mission trips are not dentists or dental hygienists. They are just very, very lovely, well-intended people who want to make a difference in the world.”

Staying busy

When Dr. Wilson is not working at his practice or donating his time to help those in need, he can be found gardening at his renovated home in Bucks County—a residence that has been featured in the Real Estate section of The New York Times.

“I’m an old soul in an old house,” he says.

Dr. Wilson also has what he called his “healthy habit” that he changes each month. This month’s habit?

“I’m being a good patient,” he laughs. “I tore my Achilles heel, so I have to wear this boot. Now I know what my patients feel like when I tell them to floss every night, because I do not like wearing this boot. But I’m learning to be a patient doctor.”

ACTIVA BioACTIVE Bulk Flow Marks Pulpdent’s First Major Product Release in 4 Years

December 12th 2024Next-generation bulk-fill dental restorative raises the standard of care for bulk-fill procedures by providing natural remineralization support, while also overcoming current bulk-fill limitations.