Affordable Aerosol Reduction

Aerosol reduction in the practice does not have to be a costly safety measure.

‘Aerosol’ has become somewhat of a buzzword since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic over a year ago. Dental practices have had to keep pace with shifting guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OHSA), and the American Dental Association (ADA).

Early on in the pandemic, in an effort to mitigate aerosol transmissions, some dental practices spent thousands, even hundreds of thousands of dollars on extraoral suction and air purification units.

The Unknown

The problem with dentists rushing out to implement often costly aerosol reduction systems, according to Jackie Dorst, RDH, BS, an infection prevention consultant and speaker, is that at the time, not enough was known about the SARS-CoV-2 virus to offer any evidence-based research on the effectiveness of such units.

“Last year as dental practices reopened after closure, there was such an unknown about the risk and concern of how we could provide safe care for patients and resume seeing them, that doctors spent thousands of dollars on their heating and air conditioning system on extraoral suction on freestanding air purification units,” Dorst says. “And yet, there wasn't the data in the research to determine how effective those devices were and [if] they were providing the protection.”

Now that more is known about the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, dental practices don’t necessarily have to invest in expensive equipment to feel confident in their aerosol mitigation efforts, Dorst says.

“Now, as we have a year of data and research behind us on both how the disease is transmitted and the effect of different devices, dentists can look at what are some of the effective yet cost-economical precautions that can be implemented,” Dorst explains.

Cost-Effective Methods

Karen Daw, MBA, CECM, a speaker and consultant known as “The OSHA Lady”, tells her clients to think about how to mitigate aerosol from the moment it’s generated instead of trying to treat aerosols that have already entered the air.

“I'm advising practices, not to only think about the aerosols in the air, but rather, how are we going to abate or mitigate aerosols from the moment it's generated?” Daw asks.

It’s a more proactive step, one that can be done with an item that is already in the operatory, she says, which is something that many clinicians probably haven’t used since dental school.

“There are some practical, low-cost things that we can do in that area too, including the use of dental dams,” Daw says. “I think that in dental school, dental hygienists and dentists all worked with dental dams, but they go into private practice, you don't really see it that often. That is a great and inexpensive way to control the aerosols—you won’t have to worry as much about what happens if it gets in the air because you're controlling it before it even gets there.”

Even though there are some limitations with using a dental dam, it’s worth implementing when possible, Dorst says.

“Now, obviously a hygienist cannot use rubber dams because the hygienist is treating all of the teeth, and again the same thing with orthodontic care. So, there are limitations. But that rubber dam provides almost complete protection against contaminated aerosols that would be coming from the patient's mouth. So that would be a huge advantage,” Dorst says.

All dental practices have a slow-speed suction and high-volume evacuation (HVE) suction on the dental unit, Dorst adds. “Optimizing HVE use during aerosol-generating procedures can reduce aerosols 80% to 94% if the suction system is functioning correctly,” she says.

It’s important for dental practices to ensure that the suction system and vacuum pump are clean and well-maintained to achieve maximum aerosol capture using high-volume extraction devices, Dorst advises.

“HVE suction should provide 300 liters per minute removal,” she says. “A dental service technician can measure the suction strength with a flow meter.”

Vacuum lines should be cleaned daily using a non-foaming, neutral pH cleaner—use of the cleaner atomizer will increase efficiency, she continues. “Always start cleaning the vacuum lines at the dental unit the furthest away from the vacuum pump and move sequentially forward—like you would sweep a floor. Change the filters on a regular schedule,” she concludes.

Hierarchy of Controls

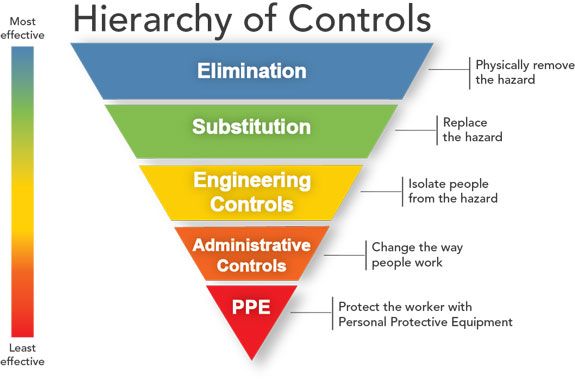

Another strategy is to fall back on infection control practices that dental professionals are already familiar with, including the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Hierarchy of Controls, Daw suggests.

“Regardless of what the occupational hazard is—whether it's standard spatter/spray exposure to bloodborne pathogens to aerosols and respiratory droplets, we should be asking ourselves “How do we totally eliminate the possibility that our team members might be exposed to this?” says Daw.

The Hierarchy of Controls from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

A common mistake she sees is people relying on personal protective equipment (PPE) as their only defense against pathogens or aerosol. However, practices should consider engineering controls

“A lot of people go, ‘Oh you know what, we'll just wear N95s, and we'll be fine. And when you think about it, that's like the last line of defense,” she explains. “The products practices are purchasing to reduce aerosol, that's an upper-level tier on the hierarchy of controls and falls under ‘engineering control’. Above that is ‘elimination’ and ‘substitution’. If these top two levels fail us—then we rely on engineering controls. And that's when we're looking at ways to eliminate the possibility that our team members might be exposed to aerosols.”

Out of the Box Thinking

Instead of rushing out to purchase the latest aerosol reduction gadgets, there are a couple of other more economical steps that can and should be addressed, according to both Daw and Dorst.

“One of the first [precautions] to be recommended by both the CDC, and by OSHA is looking at your heating and air conditioning system,” Dorst says. “It may be just changing out your regular filter that's in your heating and air conditioning system to a filter that has a MERV 13 rating or higher.”

A MERV 13 rating refers to the Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value. This will filter out 0.3 µ particles at about an 85% efficiency, according to Dorst. Since springtime is usually when practices have their HVAC systems tested for the warmer months ahead, it’s a great time to ask your air service technician about MERV 13 filters, Dorst says. These filters might be a little more costly compared to traditional particulate filters, but they provide peace of mind, she says.

Another reason to bring in an HVAC specialist or service technician is to check the practice’s air changes per hour.

“Now that means that, looking at the building size, how is the air being pulled through the heating and air conditioning system and being filtered and returned as clean air into the office,” she explains. “The recommendation for healthcare facilities is 6 air changes per hour.”

And it’s not necessarily the age of the building, but how well the heating and air conditioning systems have been maintained, Dorst adds.

Daw also recommends that dental practices work with an HVAC specialist.

“They're the ones that are going to come in and tell you, ‘Okay, here are the areas in your practice where we're not getting the optimal number of air exchanges per hour that we're looking for,’” she says. “So that could be considered economical because you're not buying anything...you're basically using what you already have in the practice which is your existing air conditioning unit.”

The CDC recently updated their ventilation guidelines for healthcare facilities, according to Daw, and there are several ways to accomplish this. Take, for example, directional airflow.

“The concept of “directional airflow”—that is, moving the air so that it flows from a ‘dirty’ to ‘clean’ direction. That completely makes sense, but I don’t think many folks think about how easy it is to adjust the air output and intake vents to create this airflow pattern,” she says. “I attended an HVAC seminar once where they showed that the correct positioning of the air vents can create a sort of ‘air curtain’. In the absence of a positive/negative air pressure room scenario, these can help to keep most of the aerosols in one area so that they can be ‘cleaned’ or ‘scrubbed’ in the air purifier or HEPA filtration unit. Other than adjusting the vents, pressure differentials can be created by differing airflow rates.”

While fans in a healthcare setting are usually against regulations, the CDC’s ventilation recommendations suggest running exhaust fans, Dorst adds.

“The CDC's also recommended that to increase the ventilation and have a little bit more fresh air coming in and reduce the concentration of aerosols and virus particles in the air, to run the bathroom exhaust fans all day,” she says. “That's going to exhaust out the air within the building.”

Fans can be used in other ways, too, Daw says.

“I know fans in healthcare settings, depending on the setting, is typically a no-no. However, the CDC references the strategic use of fans to help with moving air in the practice,” she says. “In this scenario, a fan sitting in the window would exhaust the air to the outside. Fans can also help mix the air, another way of diluting the concentration of virus particles.”

If done incorrectly, fans can create the opposite effect. Here are some tips from the CDC on the use of fans in the practice:

- Avoid the use of high-speed settings

- Use ceiling fans at low velocity and potentially in reverse-flow direction (so air is pulled up toward the ceiling)

- Direct the fan discharge towards an unoccupied corner and wall spaces or up above the occupied zone

The CDC also provides an idea of the approximate cost involved with some of these methods, according to Daw:

- No cost: opening windows; inspecting and maintaining dedicated exhaust ventilation; disabling DCV controls; repositioning outdoor air dampers

- Less than $100: using fans to increase the effectiveness of open windows; repositioning supply/exhaust diffusers to create directional airflow

- $500 (approximately): adding portable HEPA fan/filter systems

- $1500 to $2500 (approximately): adding upper room UVGI

Looking Ahead

While many practices can make these simple changes, implementing a standard aerosol reduction method in the practice won’t be a moot point, Dorst believes.

“I think in the future, there will be an ongoing emphasis and concern on aerosol and airborne disease transmission in the dental profession because of the aerosols that we do create, as we provide patient care,” she says. “In the past, we've looked at treating all patients as if they were known to be infectious for a bloodborne pathogen. I think in the future we'll look at treating all patients as if they could be in fact treated infected with an airborne pathogen, as well, such as rhinoviruses that cause a cold.”

Daw believes that COVID-19 has permanently changed air quality control.

“I don't think the virus is going away anytime soon, even with herd immunity. I think we're going to see some things permanently change as a result of this and one of them might be possibly an air quality standard,” she says.

“The bottom line is, even with HIV/AIDS, we’ve always had to implement whatever was required of us at that time,” Daw continues. “We cannot disregard that there's technology, there's PPE; if there's something that's at our disposal that is going to make things safer for us, then we have to implement it. I don’t think safety is ever going to be a wasted investment.”

“We'll have all of those aerosol mitigation precautions in place to provide a safe dental environment, no matter what the pathogen is that we may encounter when we're treating an infectious patient,” Dorst concludes.

Maximizing Value: The Hidden Benefits of Preventing Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia Through Oral Hygiene

September 10th 2024Originally posted on Infection Control Today. Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is a significant infection prevention concern, leading to high patient mortality, increased health care costs, and ICU usage. Oral hygiene is an effective preventive measure.